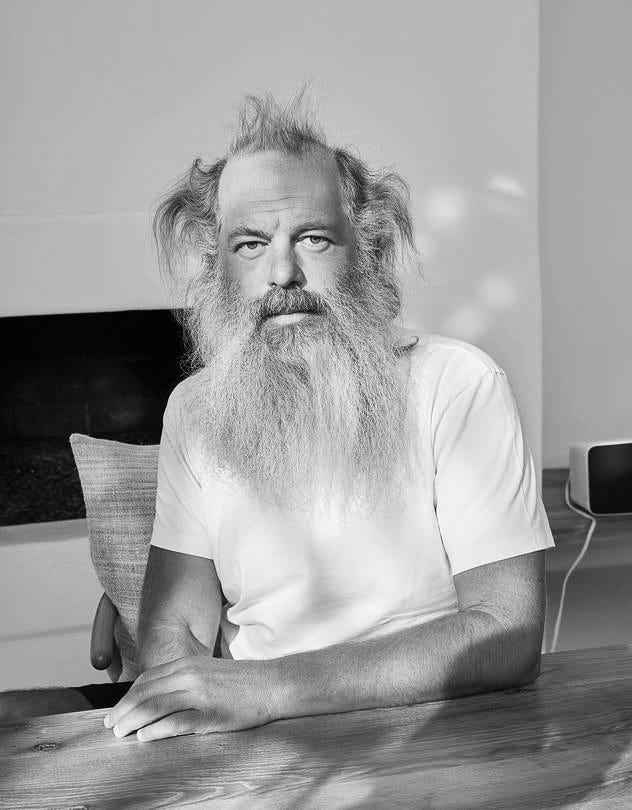

Rick Rubin: Learnings & Thoughts from "The Creative Act"

A compilation of thoughts and ideas of Rick Rubin's manifesto on creation that resonated with an investor's mind.

Art is choosing to do something skillfully, caring about the details, bringing all of yourself to make the finest work you can. It is beyond ego, vanity, self-glorification, and need for approval.

During my journey in the field of investing, I definitely took me a while to recognize that a lot of wisdom and useful experiences lie beyond the finance and investing literature, on which I relied on during the beginning. Realizing that any form of storytelling can bring an idea or thought to life, even if it's not directly related to finance, has greatly increased my motivation to read and learn because of the joy of variety. Reflecting on my latest readings, I found particular joy in Rick Rubin’s manifest on “The Creative Act”. The book is a compilation of his thoughts and experiences as an artist, but abstracted in a beautiful way that invites everyone to reflect on their own ways of being creative.

Personally, I found many of his ideas resonating with my beliefs and processes in the field of investing and my interest in writing. Classifying investing as a form of art, on a level with painting, music, and more, felt a little odd at first. However, acknowledging both the personal creative act and the craft and practice of investing as a form of art allows us to expand our thinking beyond the conventional rules and beliefs of investing, leading to new and exciting results.

Rubin’s thoughts have definitely helped me meditate on my beliefs and practices and I hope you’ll find my reflections to be of help.

Some ideas may resonante, others may not. A few may awaken an inner knowing, you forgot you had. Use what's helpful. Let go of the rest.

Lifelong Learning

Thinking about the versatile and incredible wealth of wisdom accumulated throughout the history of investing, the pursuit of lifelong learning struck me the most.

Develop into a lifelong self-learner through voracious reading; cultivate curiosity and strive to become a little wiser every day.

- Charlie Munger

While this concept can find manifestation in various forms, the habit of genuine curiosity will in every way extend our perspective and the sensibility, thereby enabling us to become an increasingly better investor ourselves. Interestingly, and perhaps induced by the significance of this topic, this concept was also reflected for me in several paragraphs of Rubin’s writing.

The heart of open-mindedness is curiosity. Curiosity doesn't take sides or insist on a single way of doing things. It explores all perspectives. Always open to new ways, always seeking to arrive at original insights.

Rubin is pointing directly at the significance of curiosity as an essential in the creative toolbox. Especially during the process of idea generation, an open mindset enables us to recognize far more opportunities due to the enhanced flexibility and sensitiveness of our mind. As with reading in particular, open-mindedness is an active way of being that demands us to constantly practice thoughtfulness and curiosity in order to connect the dots or generally extend our point of view beyond the set of beliefs we initially hold.

To keep the artistic output evolving, continually replenish the vessel from which it comes. And actively stretch your point of view. Invite beliefs that are different from the ones you hold and try to see beyond your own filter.

Challenging our own beliefs is generally the defiant part of learning, though it’s getting increasingly tougher with regard to our own investment ideas we’re holding with a high conviction after spending a significant amount of time researching. The tendency to filter incoming information and only let the confirmatory pass prevents us from doing our best work. Here, collaboration can be the next important tool. Buffett’s concept of having Charlie Munger as his sparring partner to openly discuss ideas is a popular manifestation of this concept.

When a collaborator's feedback or method seems questionable and conflicts with your default setting, reframe this as an exciting opportunity. Do all you can to see from their perspective and understand their point of view, instead of defending your own. […] In addition to solving the problem at hand, you may uncover something new about yourself and become aware of the limits boxing you in.

Rubin shared a lot of thoughts on collaboration, probably rooted in his own rule as a music producer being a sparring partner himself for other artists, which are also highly relevant for us as investors. In his writing he pictures the benefit of cooperation as giving or getting a boost to see over a high wall, therefore including no competitive thinking at all. By discussing our ideas and working together, we can accomplish results that would otherwise be beyond our individual reach.

The ego demands personal authorship, inflating itself at the expense of the art. It can reject new methods that appear counterintuitive and protect familiar ones. The best results are found when we're impartial and detached from our own strategies. We all benefit when the best idea is chosen, regardless of whether it's ours or not.

I noted the quote down to keep reminding myself that detaching from my thoughts is necessary to choose the best idea possible. Though I unconsciously feel the urge to find investment opportunities by myself, I actually know that this is only a need of my ego that I shouldn’t give in to. Especially, as tremendously helpful writings and shared wisdom was never as accessible as today. Furthermore, Rubin argues that all creative work will always be just an interpretation of the available information, which is especially important for investors, who may feel save with the takeaway from a new press release or media article, as they seem to be so clear and objective at first. The same applies to copying the ideas of other investors.

Heroes

Every artist has heroes. Creators whose work we connect with, whose methods we aspire to, whose words we cherish. These exceptional talents can seem beyond human, like mythological figures.

Thinking of cloning, we’re probably arriving at our favorite investors, our heroes. I immediately noticed the connection towards the concept of baldly copying the world’s best investors, popularized by Mohnish Pabrai, while reading Rick Rubin’s thoughts on heroes. Interestingly, Rubin points out that copying the work of other artists is not always to be condemned, since we are not in a position to copy their point of view anyway.

It's impossible to imitate another artist's point of view. We can only swim in the same waters. So feel free to copy the works that inspire you on the road to finding your own voice. It's a time-tested tradition.

So, although we have an easy access to the portfolios and latest transactions of these investors, they still seem to be surrounded by a special atmosphere. Meanwhile, this supposed transparency can be misleading, creating a false sense of certainty about the motivation (or point of view) behind these decisions.

Without witnessing a beloved work's actual creation, it's impossible to know what truly happened. And if we did observe the process with our own eyes, our account would be an outside interpretation at best.

I would never disagree with finding inspiration in the work and ideas of great investors. Recalling the fact that we’re only capable of interpreting the available data without seeing the full picture, seemed important to me though. And due to Rick Rubin’s fascinating ability to describe these human traits, I’ll end this section with his summary on interpretation and labeling:

Generally our explanations are guesses. These vague hypotheticals become fixed in our minds as fact. We are interpretation machines, and this process of labeling and detaching is efficient but not accurate. We are the unreliable narrators of our own experience.

Seeds

Seeds are a beautiful way of describing the “potential starting points that, with love and care, can grow into something beautiful.” Imagining a handful of seeds that all grow differently once planted, with no way to predict the outcome, is a helpful way to think about portfolio management. With regard to the question, what portion of the portfolio a new investment should represent, we see that there’s no right answer at the beginning. We have to start somewhere, perhaps somewhere at the lower end, and watch the seed grow. Maybe something beautiful is coming soon.

Developing this sense for the potential of our seeds can help us adjusting the portfolio allocation. Similarly, we can think of Peter Lynch’s famous analogy that selling your winners and holding your losers is like cutting the flowers and watering the weeds.

Artists are ultimately craftspeople. Sometimes our ideas come through bolts of lightning. Other times only through effort, experiment, and craft.

Likewise, we can think of seeds as simple ideas or thoughts that could appear by coincidence or as the consequence of work and effort. Importantly, the effort invested to obtain the idea doesn’t amplify the its quality.

Rules

Often the standards in our chosen medium are so ubiquitous, we take them for granted. They are invisible and unquestioned. This makes it nearly impossible to think outside the standard paradigm.

While meditating on Rubin’s thoughts on the process of idea generation, I additionally noted his sayings on rules and standards. The community of investors has constantly redefined its admired standards regarding several forms, may it be favored industries, business models, regions or valuation metrics. Moreover, we're constantly being asked to come up with a basket of labels for each idea, ranging from SaaS to Serial Acquirer to New Berkshire Hathaway and the like. While some of these labels may fit better than others, we're certainly limiting ourselves and preventing ourselves from seeing something completely new. Also, standards and labels have the fallacy to be general approaches that most of the time miss individual details. At this point, I recalled Buffett’s persuaded citing of John Maynard Keynes:

It is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong.

A quote that resonated with Rubin’s thoughts for me, influencing me to think of the necessity of adjustments we make during the analytical process. Contrary to my initial urge to calculate each financial measure according to standard accounting or even the companies’ own definitions, thinking of the rationale behind them on yourself and obtaining them as best you can, will improve the outcome more than a precisely wrong attempt would harm it. Or as Rubin summarizes:

When we make a discovery that serves our work, it's not unusual to concretize this into a formula. On occasion, we decide this formula is who we are as an artist. What our voice is and isn't. While this may benefit certain makers, it can be a limitation for others. Sometimes a formula has diminishing returns. Other times, we don't recognize that the formula is only a small aspect of what gives the work its charge. It's helpful to continually challenge your own process.

So in order to avoid the “diminishing returns” of limited perspectives, we’re circling back to being open-minded and genuinely curious. And although these conclusion may seem a little abstract, I find them really helpful to reflect on my own behavior in the process of investing. So the next time someone suggests a business or investment thesis that you'd normally dismiss out of hand because of prejudices and labels, try to redefine the situation as an opportunity to try something new or at least challenge your beliefs. Historically, this could’ve offered you a tremendous amount of great opportunity, perhaps because the effort required to be curious and to look beyond the obvious provides some kind of competitive advantage.

Invert, always Invert

Another way of getting the mind beyond existing limitations or rules is to invert the phrasing of the problem at hand.

For every rule followed, examine the possibility that the opposite might be similarly interesting. Not necessarily better, just different. In the same way, you can try the opposite or the extreme of what's suggested in these pages and it will likely be just as fruitful.

Similar to Munger before, Rubin’s description of challenging the current state relies on the old Jacobian maxim: “invert, always invert.” Nebst the concept of lifelong learning, this in probably one of the concepts that I appreciated the most practicing. Therefore, I found it useful sharing Rubin’s interpretation of it as well. Applied to problems or limitations in the creative process, trying the opposite can be really fun, even if the results are likely to be unprofitable. A good example in the investment universe was given by Gautam Baid in “The Joys of Compounding”:

What can go wrong? versus What growth drivers are there? Rather than focusing just on the growth catalysts, think probabilistically, in terms of a range of possible outcomes, and contemplate the possible risks, especially those that have never occurred.

Particularly in the field of investing, letting your thoughts wander about the opposite of your actual question can immediately ease the process. Also, playing with the opposite form of our usual practice can lead to unexpected results.

Craft

In the Experimentation phase, we planted the seed, watered it, and gave the resulting plant time to grow in the sun. We let nature take its course. Now, in this third phase, we are bringing ourselves to the project to see what we can offer.

Having collected a handful of seeds or in our case a handful of companies, we’re now actively “applying our filter” and developing the work. For me, this is reflected in my active analysis of a company or industry. Where before I was just collecting data and information, I am now ready to apply my own practice and filter to develop my own personal interpretation of the situation at hand.

However, starting this process with several ideas in mind, we can become unsure how to approach the next step. According to Rubin, we may follow the “hints of excitement” to get on a path allowing us to complete our work without getting stuck by losing the earlier temptation.

If several directions seem captivating, consider crafting more than one experiment at a time. Working on several often brings about a healthy sense of detachment.

Although every form of craft differs, I find the concept of detachment generally a useful one as I recalled my latest research attempts. Sometimes, I would analyze a particular company and really dive into without considering others as equally likely-to-buy. Other times, I would come across an industry and analyze several companies without having a particular favorite at the beginning. Although I hadn't considered it before, I always felt more confident and convinced to hold companies that were the fruit of the latter. Stepping away from a company by analyzing several ideas that excite us simultaneously deepens our knowledge overall, but also improves the results individually.

Great Works

After I’ve shared my reflections on the creative process for an investors mind, I want to end with a note on great works. Following Rubin’s thoughts, the pursuit of greatness is an unconscious desire fueled by the curious mind.

It is not a search, though it is stoked by a curiosity or hunger. A hunger to see beautiful things, hear beautiful sounds, feel deeper sensations. To learn, and to be fascinated and surprised on a continual basis.

This temptation to learn from the greatest, as a consequence of lifelong learning, returns us to the beginning of our discussion. And again, this mindset manifests itself through various forms.

If you make the choice of reading classic literature every day for a year, rather than reading the news, by the end of that time period you'll have a more honed sensitivity for recognizing greatness from the books than from the media. This applies to every choice we make.

This instantly reminds me of Charlie Munger’s approach to make friends with the eminent dead and the great thinkers of the past. By exposing ourselves to the great works, we increase our minds’ ability to “distinguish good from very good, very good from great.” The process increases our awareness for greatness and also raises the bar for our own expectations. This inspires my pursuit of learning and analyzing great companies, and also motivates me to share my reflections in the hope of satisfying my and your desire for great works.

The objective is not to learn to mimic greatness, but to calibrate our internal meter for greatness. So we can better make the thousands of choices that might ultimately lead to our own great work.

Thank you!