Idun: A Promising Contender For The Olympus of Serial Acquirers?

A not so brief story on the smallest serial acquirer I discovered so far.

Over the course of time in which I’ve studied the niche of M&A-agnostic Swedish compounders, I perceive the sky of businesses to become increasingly clear as my knowledge of a successful playbook enhances. Recently, I reflected on my experiences while thinking about a small contender in this field, Idun Industrier (“Idun”). Although the volume of keywords, e.g. serial acquirer, decentralization, high-quality businesses, etc., and their general use suggest one can hardly choose wrong among these companies, I find that there are often simple details that are capable of causing significantly different results. Therefore, while still admiring the extraordinary record of Lifco and Lagercrantz—my first ownership of serial acquirers—I am now increasingly eager to perhaps find a more hidden gem, a company that has the potential to climb the Olympus.

In my latest writing on serial acquirers, I picked several ideas that were crucial from my perspective to understand what builds a successful serial acquirer. While I find the majority of values to be similar between Idun and this group of companies, there are also small differences on which I come back later.

The story of Idun began in 2013, when now-working chairman, Adam Samuelsson, founded the company following his career at the private equity company Nordic Capital with a simple motivation: keep and develop the fantastic businesses, instead of selling them later and “throw the chips back on the roulette table and start over”1. As a consequence, Idun became a new contender in the Swedish niche of serial acquirers that are offering a permanent guardianship for the life’s work of passionate entrepreneurs. The commitment to keep and nurture these businesses with Buffett’s favorite holding period—“forever”2—lead inevitable to constraints with regard to the quality of the business, its management, profitability and cash flows.

The Playbook

The business model of Idun focusses predominantly on the development and acquisition of small- and medium-sized companies from Sweden. These companies are leading in their specific niche in slowly changing industries, generating stable cash flows, while requiring little investment expenditures for maintenance. The basic idea is that the inflow of exceeding cash is send back to HQ in Stockholm in order to finance further acquisitions. Due to the focus on a decentralized management, Idun operates closely at business level (two people of Idun in each board, always the chairman) and requires only a small overhead of around six people in the rented rooms in a Stockholm office hotel.

It suits us very well. We don't need any special premises to project anything special. In the majority of cases, we are out with the companies, both those we have in the group and potential acquisitions. That's how we work. We want to meet the entrepreneurs on site in the business.3

Personally, I really enjoy these small insights as they are remarkably helpful to imagine how the management operates and thinks. Similar to what I described as “drinking coffee” in one of my latest writings, Idun generates most of its deal flow internally by ongoingly searching for promising businesses and building relationships with potential sellers. Having a decentralized M&A approach enables Idun additionally to find interesting add-on acquisitions already at the subsidiary level, which increases the speed and flexibility of the organization. Keeping the responsibility and entrepreneurial spirit at the business level further aligns the incentives of both parties to focus on long-term value creation—not least because most of these entrepreneurs still hold shares in their companies. Overall, Idun plans with around 2-3 acquisitions a year, including one or two add-on acquisitions. However, these numbers vividly fluctuate given the deal flow, timing and size of the acquisitions as well as the strength of Idun’s balance sheet. As Karl-Emil Engström states to this regard: “We would rather do zero acquisitions than the wrong acquisition”.

Another aspect worth highlighting is Idun being a sector-acnostic serial acquirer, thereby constantly expanding its circle of competence and field of potential add-ons. In contrast to strategic buyers, the company does not pursue synergies, which diversifies the group portfolio and reduces the potential downside of the purchase price paid. At the same time, seeking to find high-quality companies in once circle of competence at low multiples inevitably leads to “boring” industries and businesses that can appear unattractive at first sight. Therefore, I looked at the group companies a second time and prepared a small overview of Idun’s cash flow contributors.

Group Companies

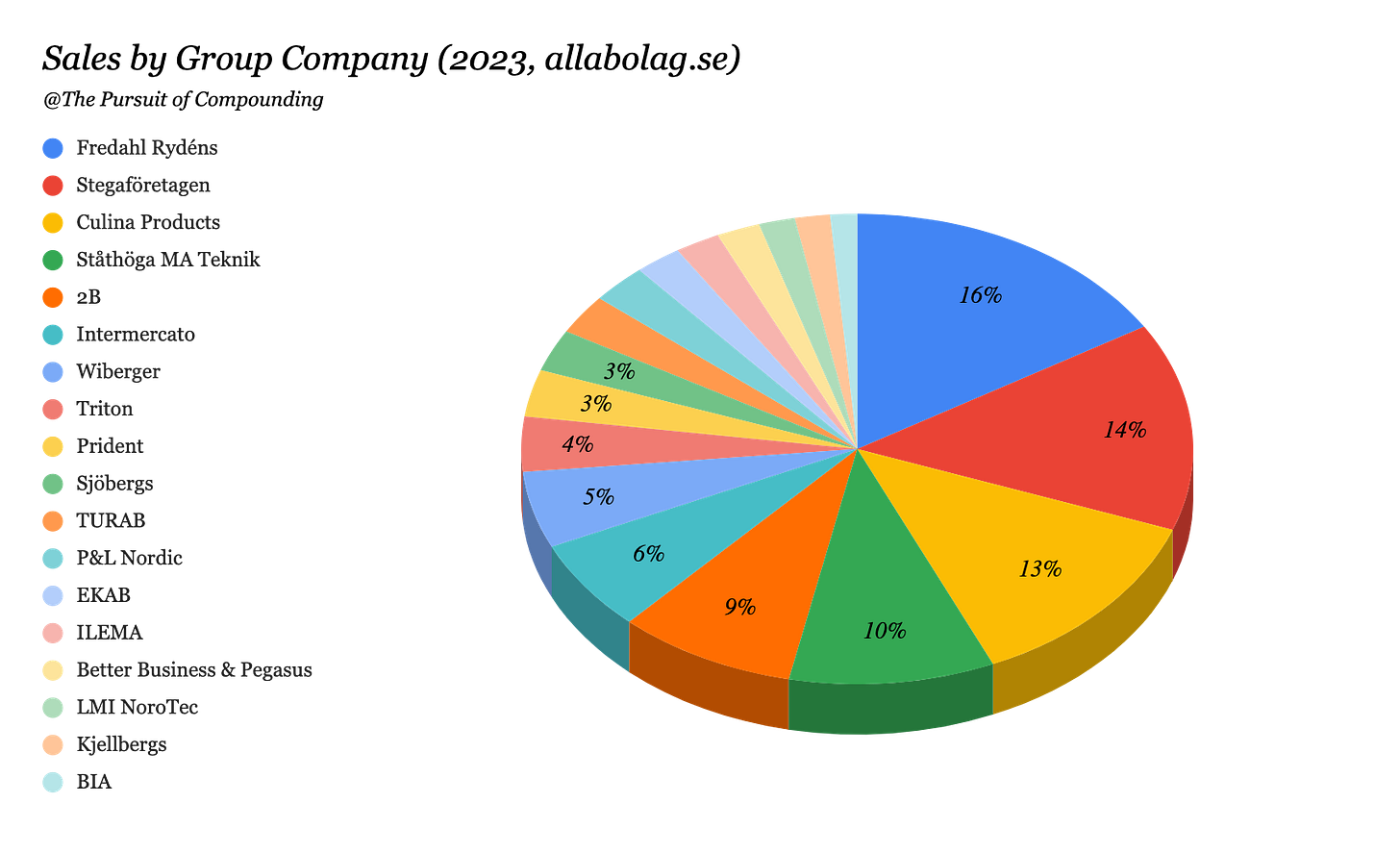

The group portfolio currently consist of 18 businesses, which are categorized in the segments: Manufacturing, and Service & Maintenance.

Stegaföretagen (“Stega”) initially started with Prowash, the leading provider of complete service and product offerings to the wash operators in Sweden and Finland. Additionally to organic growth, the group acquired further car- and washing-related businesses over the years, and as a consequence currently consists of six operating subsidiaries. Interestingly, Stega appears to be a small serial acquirer on its own of which Idun holds 49% since 2014. Due to this below-average ownership and and the operating model, Stega represents a special case in Idun’s overall group. While the business seems to post solid returns, we should notice that the missing majority stake is definitely hindering the Group to access exceeding cashflows.

Fredahl Rydéns is the newest and largest acquisition of Idun to the time of writing. Consolidated in March 2023, Fredahl Rydéns offers a complete range of mainly chests and urns to funeral homes in Scandinavia. Recently, Carnegie Research published an extensive research report on Idun and estimated Fredahl Rydéns’ market share to be around 55-60%, which already caused an investigation by the Swedish Competition Authority in 2017/18 (later dropped). Overall, the company appears to be a great exemplary acquisition, combining the core ideas: stable and predictable cash flows, market leading position in a niche, circle of competence and co-ownership with the family.

Culina Products contributes approximately 13% to Idun’s top-line through the manufacturing and distribution of equipment for commercial kitchens in Sweden. After initiating this small group in 2021 with the acquisition of Culina Products AB, the subsegment is now combining the six operating businesses—thereby representing a good example of using add-on acquisitions to built on existing industry expertise and further consolidate market share. Overall, these businesses are expected to have around 50% market share, while most of their customers are operating in the public sector.

In addition to these examples, Idun’s group companies have exposure in the markets for material handling, healthcare and various industrial niches. Therefore, I find Idun’s sales to be widely diversified, which complements my ideal of a sector-agnostic “classic” serial acquirer—also visible as the Swedish word for synergy appears 0x in Idun’s annual report.

Profitability

Although synergies are apparently not focused by the company, Idun grew its EBITA by 41% annually—even outpacing the revenue compound rate of 37% since 2015. Last year, the EBITA margin decreased to 13.7%, after finding its peak in the year prior. The large acquisition of Fredahl Rydéns can be named as a reason, as the market leader is expected to achieve an EBITA margin of around 9%, thereby diluting the overall margin. In the coming years, however, Idun’s group companies should be able to benefit from their leading positions and increase profitability—narrowing the gap to the weighted average of 15%, which I obtained using the company’s acquisitions since 2019 and the respective annual sales/EBITA estimates.

Over the course of a business cycle, Idun targets to achieve an organic EBITA growth of about 5% per annum with its group companies, thereby contributing 1/3 to the overall growth target of 15%. Unfortunately, Idun didn’t disclose the organic growth rate constantly in the last years, but the expected growth for the industries mentioned above would probably result in a similar assumption.

Acquisitions

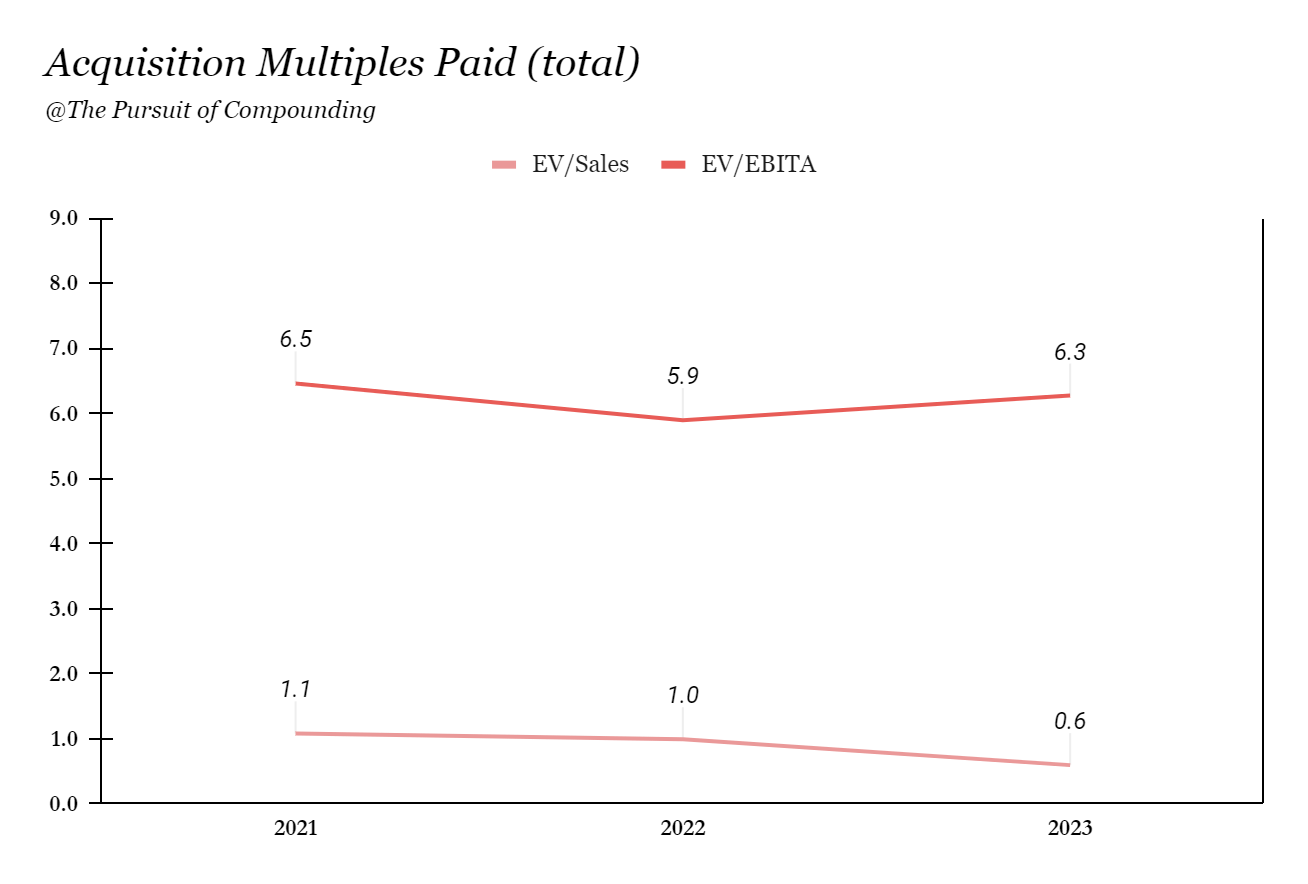

Another aspect of Idun’s generation of shareholder value lies in their ability to buy these companies at attractive prices in order to obtain a decent return on the invested capital. According to Engström’s comments at a presentation this year, Idun acquires companies at around 6-8x operating profits, which is quite in line with the Swedish peers.

Unfortunately, I have only been able to accumulate the disclosed purchase prices since 2021, but the findings reinforce the range given by management. To this extent, I would like to emphasize that such an analysis is always lacking the “normalized” earnings that the management of serial acquirers apply themselves.

Looking at the capital returns of Idun, however, we still find some headroom left in comparison to its peers, especially due to a lower sales turnover and the diluted margin. This is already being addressed by management’s efficiency measures, which could narrow the gap if they bear fruit.

Co-Ownership

As already mentioned, Idun follows several ideas and principles of successful serial acquirers. However, while most of them are acquiring 100% of the targeted company, Idun prefers a “co-ownership” approach and usually buys only a majority stake of around 70-90%—leaving or selling the remainder to the operating management. Idun also enters complete ownership, but generally prefers to share interests with the management, which aligns incentives to focus on long-term value creation instead of a relatively narrow earn-out period. As a consequence, Idun’s financials come with a twist. While the group companies’ performances are fully consolidated (despite Stega) within Idun’s Group results, each remaining minority shareholder receives its share of the pie before the ordinary shareholders in Idun come to the turn.

Currently, Idun’s shareholders receive around 76% of the reported EBITA, thereby indicating the average ownership in the acquired businesses. As mentioned earlier, the decentralized organizational structure and the minority shareholding are a great way to align interest in the group companies. Idun highly emphasize this approach using Buffett’s phrasing “we eat our own cooking”, while also referring to the fact that the founder and working chairman, Adam Samuelsson, still owns 31% of the capital and even 81% of the voting rights. Karl-Emil Engström, the current CEO, owns 140,000 shares, or about 1.3% of Idun’s capital, which also accounts for most of his net worth.

Implications for Cashflows

The flipside of this additional incentive lies in the increased complexity of assessing each companies’ cashflows or even more to analyze the cash available for acquisitions.

Firstly, Idun can access most of the group companies cash flows without difficulties due to the majority shareholding—the only exception being Stegaföretagen as Idun only holds 49% of the company. However, by using dividends at the subsidiary level, Idun can generally get liquidity up the structure very effectively. In addition, the company recently set up a cash pool, which combines the liquidity reserves of currently 8/18 subsidiaries. From my perspective, seeing these challenges addressed underscores the fact that management is constantly thinking about how to allocate capital and how to improve Idun's cash flow and thus its ability to make further acquisitions.

Financing

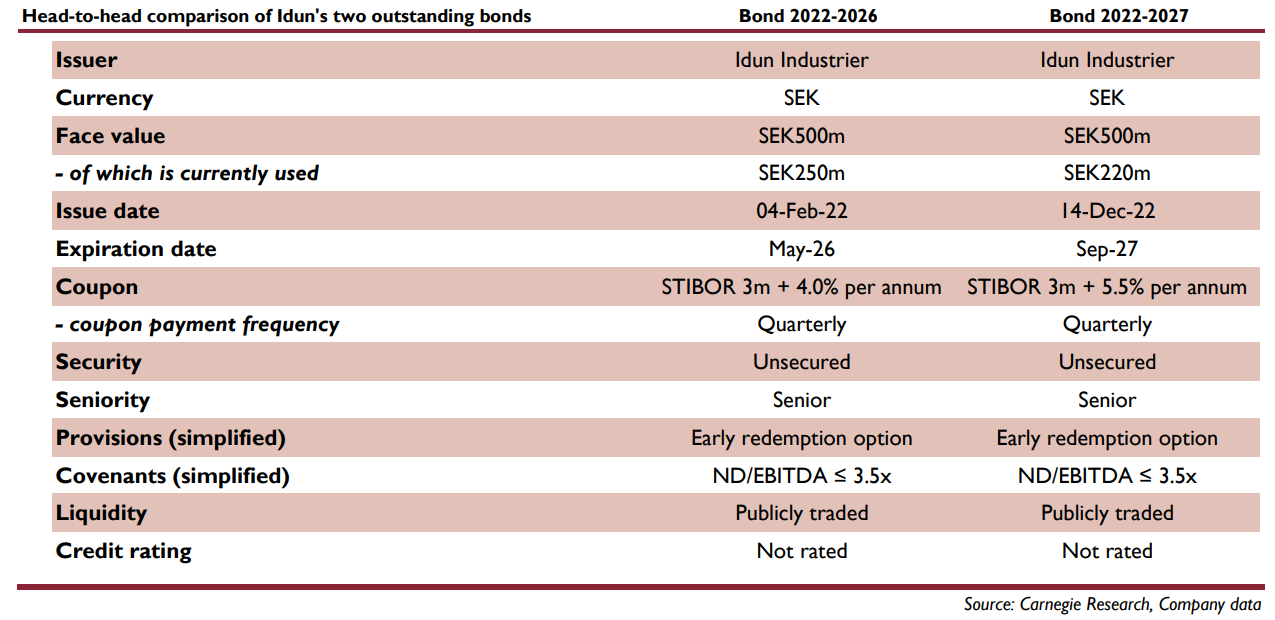

Idun’s past performance was built on the solid cash flows of its specialized group companies. However, Idun's outstanding growth in recent years has been achieved through a remarkable buying spree. Since the beginning of 2021, Idun has already acquired 12 companies, thereby spending on average 240% of its operating cash flow on M&A. This kind of “kick-start” was fueled by the IPO proceeds in 2021 and two bond issues in 2022.

As a consequence, we find Idun’s leverage to be higher compared to e.g. Lifco or Lagercrantz, who achieved their extraordinary track records without really exceeding a net financial debt of 2x EBITDA. Especially, in current times of higher interest rates, Idun faced constantly rising interest payments—with more than 50% of those resulting from the issued bonds.

The combination of an increased leverage and fast acquisition pace lead to the assumption that 2024 is likely to be a year of “normalization”, maybe with an increased internal focus on decreasing financial liabilities and working on efficiency measures. Yet, Idun is of course continuing their search for promising companies, building relationships and so on. But the management as well knows that a successful serial acquirer requires financial strength in order to be bold and fast when opportunities arise.

As we mentioned in the last quarterly report, our intention during the year is to use the group's good cash generation and strong cash position in part to reduce gross debt in order to improve capital efficiency and net interest, and we have during Q1 in a first step amortized debts with approx. SEK 115 million. (Q1 Report, translated)

As a consequence of these amortizations, Idun currently states a net debt to EBITDA ratio of 2.4x, which leaves enough room to the bond’s covenant and financial target of below 3.5x. However, one should not forget the company’s dividend payments to minority shareholders, which reduce the cash available for debt repayments and increase the somewhat actual coverage ratio.

Cash Flows

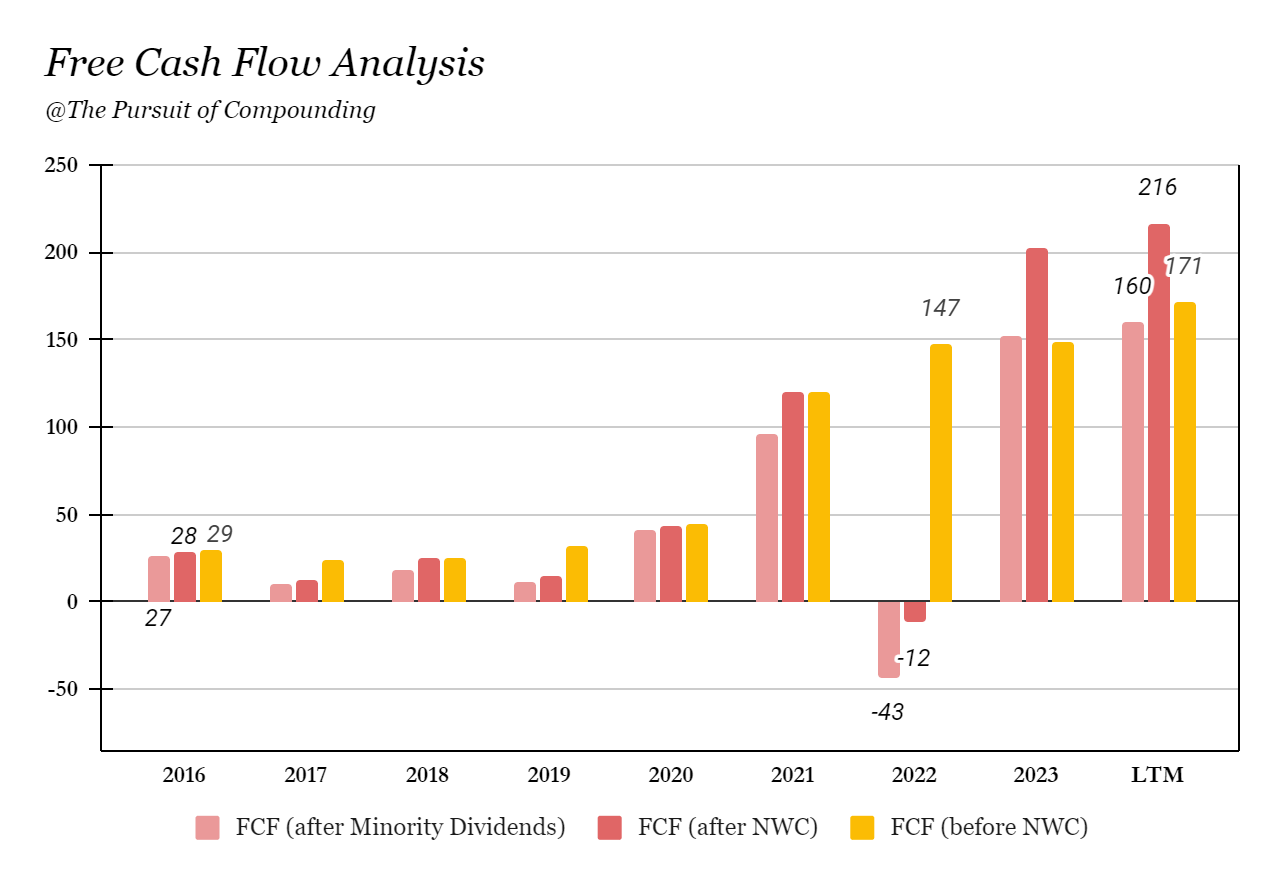

During the last 12 months, Idun spotted a solid cash conversion of 76%, which increased significantly over the last years compared to about 50% in 2015. Reducing the operating cash flow of 260m SEK with capital expenditures of 44m SEK, we derive at a free cash flow of 216m SEK.

In addition, I usually monitor the free cash flow excluding the movements of working capital in order to understand the underlying cash flow without its short-term distractions. The case of Idun likely showed the largest temporarily diverge so far as a consequence of a significant inventory build-up and rise of accounts receivable in 2022. In the annual report, the management addressed the situation and the measures taken with a focus on the working capital, which has worked so far, as the figures for the following year have shown.

It is in itself nothing unusual for the group to show a strong operating cash flow, but perhaps rather a reasonable expectation of a "normal year" (given e.g. strong niche market positions and relatively good margins) but it is none the less gratifying to state that measures taken during 2023 concerning not least inventory levels have borne fruit. Most of the correction work may have been done, but we will continue to maintain a focus on working capital in 2024 as well. (Annual Report, translated)

As I write this, I really appreciate the work of management with opportunities and challenges, as their clear communication and hands-on mentality seems to be a recurring pattern across different themes.

Valuation

Idun currently trades at 239 SEK per share, equalling a market cap of about 2.54 billion SEK, 219 million EUR or 1/50 of Lifco. To get a grasp on the current valuation, I predominantly use EV/FCF and EV/EBITA multiples, which are obtained using the underlying FCF (excl. NWC changes) and the EBITA attributable for Idun’s shareholders.

Following the IPO in March 2021, Idun’s share price rose immensely similar to various serial acquirers at the time. However, probably a mix of “normalization” in market valuations and the higher interest rate environment caused the stock to enter more reasonable valuation stages. Currently, Idun is priced with about 15x EBITA and 19x free cash flow, thereby indicating more cautiousness towards future growth rates than we find at sector-agnostic peers like Lifco, Lagercrantz or Momentum Group.

This could be the consequence of a shorter track record and significantly higher net debt to EBITDA ratios. In the past of serial acquirers, running too fast was often a mistake in hindsight, due to issues with interest payments, shareholder dilution or the quality of acquired businesses. Therefore, it is crucial for a successful serial acquirer to maintain a high hurdle-rate and persistence when it comes to business quality. Idun’s run over the last years was excitingly fast, but simultaneously rises uncertainty for the coming years. To this extent, I find the management of the company to have the right mentality, demonstrating the ability to focus on internal efficiency measures and debt reduction instead of blindly pursuing empire building. Nevertheless, it remains to see how the acquisition pace and organic development of the group companies evolve over time and cycles—thereby answering the question, whether Idun will close the gap to proven serial acquirer peers.

Conclusion

I find Idun to be an interesting new contender on the map of Swedish serial acquirers, following proven strategies and lead by a highly-motivated and experienced management team. The company already demonstrated its ability to find and acquire market-leading companies that are able to grow top-line and margins organically over time without being too exposed to cyclical industries. In addition, Idun set up a good incentive structure to ensure long-term focus and entrepreneurship across the whole group, thereby also enabling subsidiaries to benefit from add-on acquisitions without overruling them to achieve certain synergies.

On the contrary side, I find myself struggling with the very high acquisition pace over the last years, which could only be financed by raising additional equity (IPO) and debt (although they were likely various other reasons to go public). While I would hope that Idun reduces its debt further and continues its M&A journey more in line with its cash available for acquisitions, I understand that the short, but intense history justifies a discount towards the Olympus of serial acquirers.

Thank you!

I translated an interview in Swedish from 2022.

Warren Buffett, Chairman’s Letter, 1988

A translated quote from Karl-Emil Engström in Affärsvärlden, 2022